In Kooperation mit Trekk’n Guide

The blister on my ring finger started to hurt. My living room was covered in a layer of fine birch dust and wood shavings were scattered around my apartment. After a long day of rasping, filing and sanding, I lay tired in bed. Wood shavings pricked my leg. It didn't matter, because my first self-made knife was lying next to my bed. Soon a second and a third knife were lying next to it. I wanted to know more about knife making, especially about the small details that kept tripping me up in terms of craftsmanship. In November 2023, I joined a knife-making course run by Trekk'n Guide. Christoph Maretzek, the founder of Trekk'n Guide, built his first knife back in 1982 in a scout group. Christoph can't say how many knives he has made in his life. But one thing is certain: every single one is unique and a reliable companion on tours.

I asked Christoph to write a guest article for Fernweh-Motive to take us into the world of traditional knife-making. By the way: Christoph is also the founder of the Guide Academy Europe, where I did my training as a trekking guide. That's when I saw his self-made knives for the first time.

Enjoy reading!

Guest article by Christoph Maretzek

Christmas Eve 2023, a small hut in the northern Black Forest.....

So now the car is standing still in front of the hut again. The year is coming to an end, the world is rumbling... what could be better than treating yourself to something good...? The tools and pieces of wood for a new knife are looking at me on the table. For days now, many ideas for a new piece have been running through my head and slowly forming into a picture. I've often been asked why I keep making a new knife when I can only use one? Well, because it simply brings satisfaction and relaxation, challenge and maximum concentration all in one. And just as some men have several wristwatches and some women have several pairs of shoes, as an old man of the woods I have several knives to choose from.

The creative part of knife making doesn't start with the tools, but always with an idea or many ideas. It is similar to a painting - it is first developed in the mind. The holiday soup from the can has now been eaten, the last Swedish crumb coffee from the summer has been boiled for the third time on the old stove and almost everything is as it should be on this day. The fat duck is gently simmering away in the old kitchen witch and can safely stay warm for another 2-3 hours. The roast for tomorrow and the day after tomorrow. Outside, the old beech and Douglas fir trees are bending in the strong gusts of wind. Contemplation, peace, and contentment with the opportunity to once again build a small knife here in the inner silence. And the best Christmas present is peace and quiet. Only the storm's roar outside makes me sit up and take notice. After all, an old hut like this is not a bunker with a concrete cap.... You have to listen carefully.

Here we go. As is so often the case when building a knife, my thoughts turn to the shape, form, material, and arrangement of the components, but after 10 minutes of faltering scribbling on the pad, I put everything aside, somewhat annoyed, and put it off until tomorrow. It's not really taking off tonight. My head is still too full. That can happen when you're working artistically....'s not a problem.

But writing is already much easier for me! There's so much I could tell you about what I've done in almost 40 years of knife-making and what I might still do. There's no shortage of ideas 😊. So, let's whip out the electronic pen, rinse our throats with freshly prepared pine schnapps, and get going.

Doch das Schreiben geht mir schon deutlich leichter von der Hand! So vieles könnte ich berichten, was in nun fast 40 Jahren Messerbauen war und vielleicht noch sein wird. An Ideen mangelt es nicht 😊. Also, zücken wir mal die elektronische Feder, spülen den Rachen mit einem frisch angesetzten Zirbenschnäpslein und legen mit Schwung los.

Click here for Trekk'n Guide and the Guide Academy Europe (GAE).

The knife-making courses can be found here, current dates for 2024 will be coming soon.

Knife-Making - an ancient Craft

This usually makes the men's eyes glaze over. And only rarely do they voluntarily reach for the small blades. Somewhere in them, the value of a strong blade still seems to be anchored today. Or is it just boredom in the office and in front of the computer... hm. The dream of a great touring adventure... who knows for sure. Except that today nobody needs a short sword, cutlass or a long hunting dagger anymore. A 10 cm blade does the trick and is also compliant with the local weapons laws. The ladies are often a little more reserved and don't associate their knives with fighting, hunting or adventure. They often seem to me to enjoy the building itself rather than the prospect of sending their inner Jack London into the woods :-).

Knife-Making Courses with Children

Knife-making courses with children are different. All sorts of things are mixed together and the greatest adventure for the kids is to be able to do it themselves at the end. In our high-tech and increasingly virtual world, this is probably the greatest adventure for them! And anyone who says that children can't get involved in something for eight hours has either studied wrong or simply has no idea about kids and crafts!

The last knife-making course in snowy November this year once again clearly demonstrated this. If you instruct children properly, get them excited instead of just stuffing them with knowledge and forcing them to sit still, challenge them, and not bore them, then they create real little works of art. And their safe handling of sharp tools, well demonstrated and shown, exemplified and, if necessary, clearly enforced, is no problem at all. There are sometimes small cuts in their fingers...but they usually learn from them faster than many adults. Dozens of courses with youth and adult groups since 1983 have always been a feast for the senses and the eye. And many a time I was delighted when a former participant came to a camp years later and showed the good piece around.

1982...back to the Beginning: the first self-made Knife

Almost 40 years ago, we were sitting with Balu, an older scout leader, doing autumn crafts at the Handwerkerhof, a scout meeting place in Bauland near Mosbach, and were happy because we eight boys and girls had got one of the rare places on his knife-making course! Balu carefully unpacked the blades he had brought from Sweden and poured out a bag of pieces of wood, deer and reindeer antlers on the beer table set under the old walnut tree.

The quiet passion that gripped me that day will probably only leave me when there is no more steel for blades or when my fingers can no longer hold a tool due to gout:-). But that will certainly be a while yet. And I'm sure I'll get into trouble in the old people's home when I'm once again up at 2 a.m. at the kitchen table fiddling with tools and dusting everything with grinding dust and horn flour.

Magic Move...Timestep: Knife-making Course at the Outdoor Camp

First the Sketch

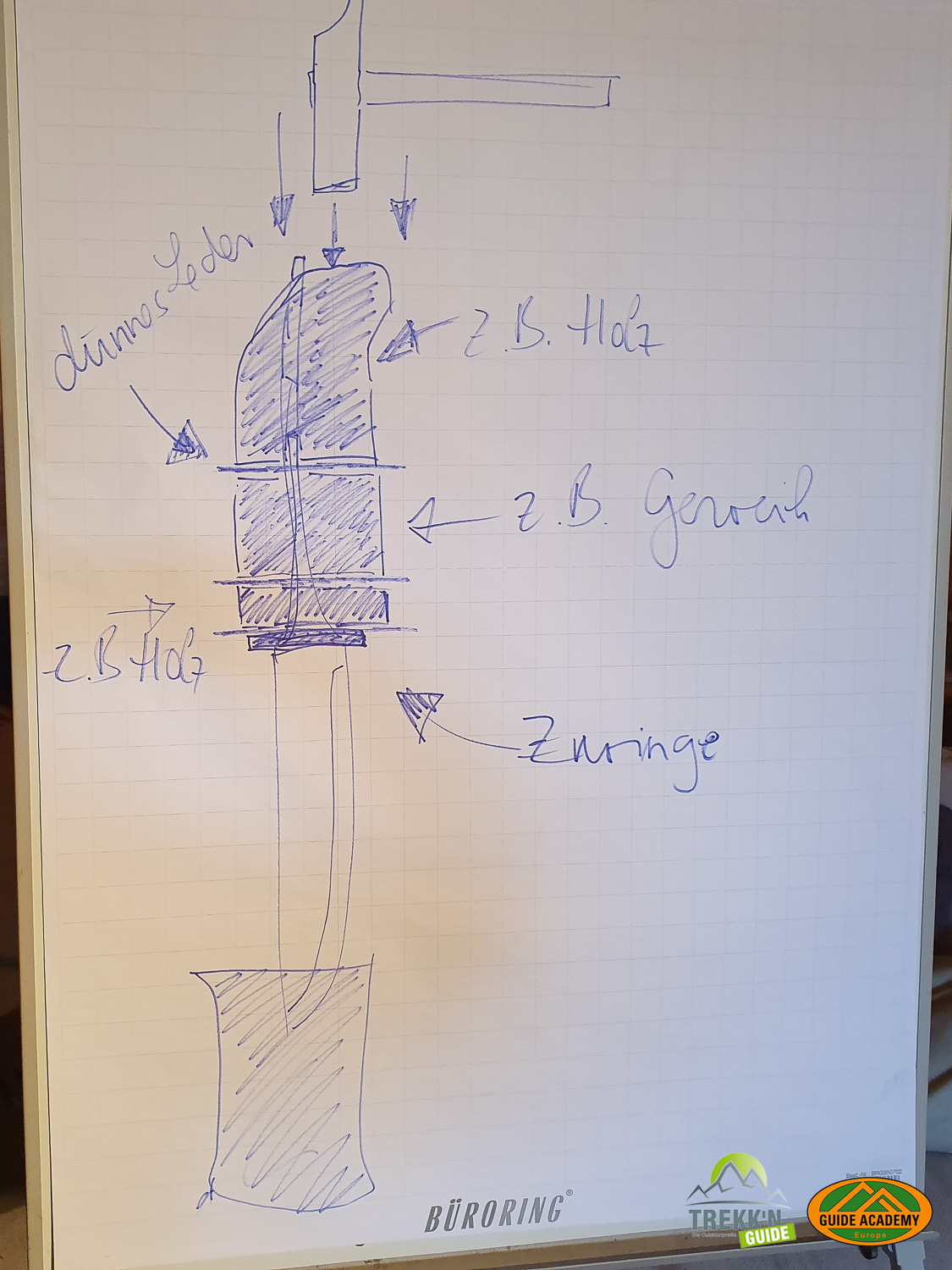

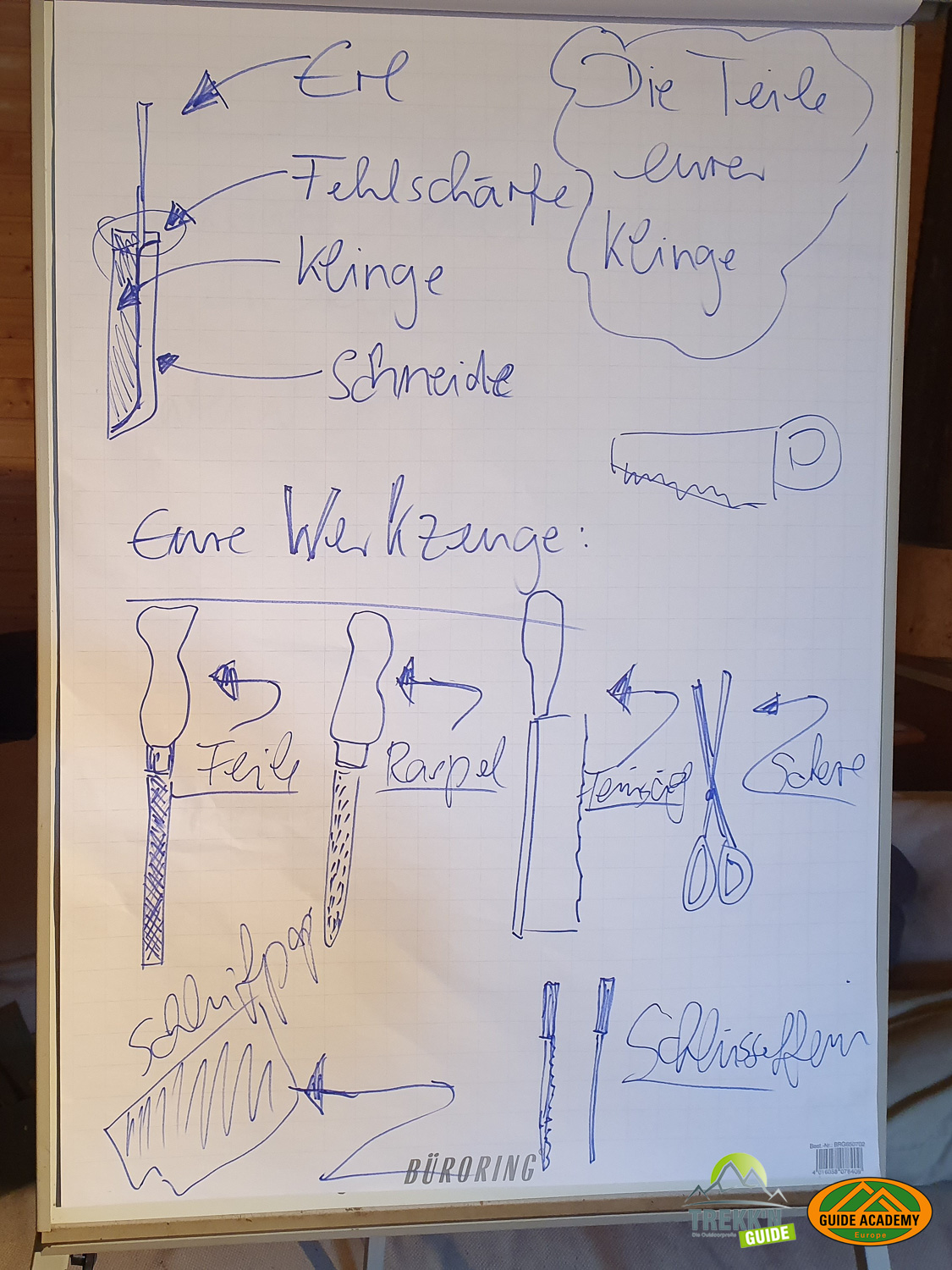

Almost 40 years later, I have the honor and pleasure of repeating the same magic on screwed-together beer table sets in November 2023. And now I'm the older one from back then. In 1982, just like today, everyone grabs a blade and the other components are quickly grabbed with nimble fingers. It was all very brisk, but peaceful. The restless anticipation was certainly in our eyes back then, just like my knife-making guests at the 2023 camp. Everyone turned their stuff back and forth in their hands and after just a few minutes, a 1:1 sketch was on paper.

Then the Tools

A few corrections here and there and everyone is already sitting at the small vices quickly screwed to the beer tables and starting to grind the slot for the tang into the front fit and some other components of the handle. My job is to immediately and reliably recognize where the user still has room for improvement in their craftsmanship. Similar to a shooting instructor on the range, the error must be quickly recognized and named in order to quickly and safely implement the correct handling of unfamiliar tools without any prior practice. A piece of horn or a drilled-out handle blank is quickly rendered useless if the tool is not handled correctly. The time factor is also important because a weekend at the winter hut also ties up time for chopping wood, firing the stove, pitching tents, cooking, and hut duty. A weekend is quite short. It has to run smoothly.

Only a rasp, fine saw, carving knife, hammer, and sandpaper are used in the knife-making course. That's all the equipment we need! There is a small power generator outside for support with a belt sander here and there, but the small craftsman's yard is actually at work here. As with the old Sami, whose style has inspired me for 40 years, we go about our work literally over the knee, i.e. without heavy equipment, just with our eyes and muscle power.

Knives...a Fascination, almost as old as Mankind

Even if today knives are regarded as weapons almost per se, Sami, or actually even Nordic knives as a whole were and are not weapons. They are not descended from cutlasses, bowie or sidearm. They are one of the most versatile small tools for outdoors and the ones we build have nothing in common with the pseudo-military style tusks from the relevant survival stores. However, this is something that needs to be communicated quite emphatically nowadays, because the media and hearsay have given everyone an "opinion", often without any idea. In Norway, Finland, and Sweden, knife-making is a traditional cultural asset that requires a great deal of judgment, patience, determination, knowledge of wood, tool mastery, and creativity. In some cases, the correct use of knives for outdoor activities is even taught at school.

Anyone who builds knives and concentrates for hours while doing so does so in the same way as a good mountain hiker. If too much wood breaks away, the beautifully shaped bow that has been created over hours of perseverance and persistence is ruined in the handle. And every time, this very flaw will catch the eye like the tiny, unsuccessful wallpaper corner in the living room, right in the corner of your eye above the TV....:-).

So the noisy world has to stay outside for a while for it to work. If it succeeds, and if the knife ends up being faithful and stable for decades, it is a pleasure to use it on tour every time. And perhaps to pass it on to a friend at the end of the tour. Well, as my touring life after 40 years will also have a foreseeable end in 10 or 20 years at the latest, I have already decided on the next owner for one or two of the knives I have built.

For my old sergeant comrades from the mountain troops, with whom I enjoyed serving for a very long time, I have been making small knives for two years as a thank you and a timely farewell. We are still in contact, but we only see each other very rarely. I have many of the boys and girls in my heart and a little knife seemed like a fitting gift and thank you. Because loyal sergeant comrades on the mountain are like good knives in a rucksack... they don't grow on trees and the relationships grow like the knife under your own hands. It is up to the adults to set an example and, if necessary, to address this. When the war started, I spontaneously made and sent one to the President of Ukraine... with the wish that he and his compatriots would soon be able to go hiking and fishing in peace again.

For me, all of this is part of knife making. After all, a knife is a skillfully crafted, elegant and beautifully shaped tool that is only used as a tool. As a gift, it can be a highly personalized object that is tailored to finger length, left- or right-handedness, intended use, personal preferences and hand diameter, for example.

The Sami Knife

The Knife Blades

Traditionally, Sami knives were and are made from simple, high-carbon blades. They are not highly refined and can therefore be easily resharpened on any stone or ceramic cup. They are available polished or scaled. Like the handle, they develop a patina over the years and are either rust-resistant or only rust-resistant. Many people in the country reflexively buy a stainless steel blade...but are almost never able to sharpen or keep it sharp themselves.

In combination with an aging handle, which becomes more and more beautiful through sweat and dust, grease, and wax, the aging carbon blade is no harm! Quite the opposite, because it is the matching counterpart, and only as a whole does the living unit please the eye of the beholder. Who hasn't seen it before? A beautiful, old, well-maintained, and darkened leather is appealing. And so the knife sheath also becomes part of the whole. It is not for nothing that Sami knife making is considered a high school of craftsmanship throughout northern Sweden.

Purchased, self-searched or self-made

Today, we use blades made in large quantities in Sweden, Norway and Finland. In 1982, there were no knife makers as we know them today, nor were there any dealers who stocked Swedish blades. You had to buy them in the country and bring them home, just like the reindeer antlers, which you had to look for yourself in the fjäll and then carry with you in your backpack, which got heavier and heavier every day. Birch tubers were easily cut from the tree and dried at home for 2-3 years. Today, everything can be bought and the laws have changed. But for my own knives, I still use the long treks in the north or in local forests to look for beautiful things and prepare them myself. Within the framework of today's laws and the sometimes changed views.

I buy some parts such as blades or finishes for the knife-making courses, and sometimes also very beautiful pieces of curly birch. But more and more I am returning to my own origins. I collect the wood on extended tours and more and more often I make my own blades from old files or grind old blades. And more and more often I try my hand at forging small blades because there is something magical about shaping a blade from an old stonemason's pestle and hardening it yourself using simple means. And year after year it gets better, because even today it's trial and error, try again, and even today only constant practice makes perfect. Sometimes I give them to a professional company for hardening if my gut tells me to. Sometimes I give them to a professional company for hardening if my gut tells me to.

The Materials for Knife-Making in the Sami Style

Handles and sheaths were and are traditionally made of reindeer antler, elk antler or bone, mixed with brass and silver fittings, combined with birch/willow or alder wood. Today, with the possibilities much finer than the beautiful old pieces that can be seen in some huts or museums, completely different woods are also used in the north. Some of the most beautiful old pieces can be admired in the Samimuseeum "Aitje" in Jokkmokk . The eyes of anyone interested in handicrafts will be wide open. What the guys were able to build without workshops, in the evenings by the fire in their lavvus and kotas, is simply enchanting. Attempts to do the same have certainly been successful. Even without a workshop, you can do a lot if you have practiced it often enough with full equipment beforehand. then the hand movements are right and you can come up with something without a lot of tools.

Gluing or Clamping

In those days, the old knife makers did not yet have epoxy resin, machines, or numerous tools. Their main tool was usually another knife. And in Lapland, not all knives are the same! Many Sami had several knives hanging on their belt at the same time, as each had its own purpose. They made their own glue: Natural resin, mixed with grated charcoal, fine fibers, and wax, made a stable and durable glue in the right proportions. Sometimes also simple, boiled birch pitch with sawdust or fibers. However, the absorption of the large forces in the handle was usually ensured by end rivets and a very tight construction. Large-scale pouring, or rather rough smearing with synthetic resin, as shown in some YouTube videos... that didn't exist. And those of us who are guided by this craftsmanship today use as little synthetic glue as possible. The old role models always spur me on.

Even the ancient Sami, other peoples living in the north, such as the Nenets or Siberian ethnic groups and the ancient Vikings knew about the art of making a knife from birch bark slices and attaching it without any glue! This can also be done with other bark, but it is a lot of work and requires some experience. Except for Mareike, the owner of the blog "Fernweh-Motive". With her solid technical training and experience, her keen eye, and a real feel for her fingers, she has been conjuring up enchanting pieces for a year now. In a quality that took me years of practice without any instruction! She now benefits from some guidance and she is a real natural.... with leather as well as wood and metal.

Building simple Knives yourself

About "simple Craftsmanship" and following the Rules

"Simple" is often all too quickly seen as "cheap" or not so artistic, especially by young participants with no craft experience and often blessed with more theoretical knowledge than practical skills. They also often question tried-and-tested craft techniques without hesitation or carelessly reject necessary usage specifications for materials and tools. With a view to safety and correctness, it is sometimes necessary to draw boundaries and, as an instructor, convey that "simple craftsmanship" is largely based on adherence to rules in addition to creativity. And that "simple" refers more to the equipment than to the processes, hand movements, and the result. Building a knife that lasts outside is not exactly easy or simple. Otherwise, a tool will quickly get stuck in your finger. And building it in such a way that it is not sent Amazon style "ordered today, delivered yesterday", can also grow step by step. This is a real collision with today's world.

However, after 10 hours of honest manual work, this initial misjudgment usually disappears quite quickly. It is quite "simple". If you stretch your aching hands and tense back, you can feel it "in your bones". And there is no better barometer.

Don't get your expectations too high at the beginning, because even if clips promise "you can do anything", it's not like that. Someone making their first knife should be guided by their own ideas, not by the skills acquired by the instructor through countless sample knives. Something like this has to grow continuously. You can quickly learn the basics for your own knife with good instruction. For the rest, you need your own eyes, ideas and growing dexterity. Step by step and sometimes with failure. With time and perseverance, you'll get there. Practice makes perfect and cannot be learned at the weekend. Rare exceptions like Mareike only confirm the rule... 😊

Man hänge am Anfang den eigenen Apfel der Erwartung nicht zu hoch, denn auch wenn Clips „du kannst alles“ versprechen, ist es so nicht. Jemand, der sein erstes Messer macht, sollte sich an seinen eigenen Ideen, nicht an den durch unzählige Übungsmesser erworbenen Fähigkeiten des Anleiters orientieren. Denn der hat ja erheblichen Vorsprung und das holt man nicht eben auf. So was muss kontinuierlich wachsen. Die Grundlagen als Basis für das eigene Messer lernt man schnell bei guter Anleitung. Für den Rest sind dann die eigenen Augen, Ideen und wachsende Fingerfertigkeiten nötig. Schritt für Schritt und auch mal mit Misserfolg. Mit Zeit und Ausdauer wird es was. Übung macht den Meister und ist nicht mal eben am Wochenende erlernbar. Seltene Ausnahmen wie Mareike bestätigen nur die Regel…😊

Sanding and oiling

And when this first knife slowly takes shape under a rasp and file, when it is oiled for the first time after being sanded with fine sandpaper, it comes to life. The heat from polishing opens the pores and the oil penetrates deep into the wood. The different dense wood structures absorb the oil differently and become lighter or darker in color. We call this "firing up". When the group then comes together and enjoys the afternoon they have spent together with so much effort, praising each other and sharing in the joy of the other builder's knife, then it is time for me as the instructor to step back for a moment and let them get on with it. They have truly earned it.

How often have I enjoyed seeing the participants' eyes sparkle with joy in these moments. That joy when we fired the new knife together for the first time with linseed oil and beeswax, when all the depths and inclusions in the wood were suddenly emphasized. That's when I calm down a bit too. THAT is MY reward.

The participants are rightly proud and in a short time I have taught them to make something really beautiful for themselves and with their own hands. To most inexperienced observers, it looks easy. But simultaneously "co-constructing" several knives in the making with the eye and the head, usually with strangers, demands all the senses and binds the attention for hours. As an instructor, you have to recognize the possibilities of the wood, as well as the conceivable shapes and combinations, and also tease out what the participant has in mind. This doesn't always work straight away and some young people need to be shown the value of life experience and craftsmanship rather than simply learned knowledge. This calls for pedagogical skills and verbal acrobatics as well as the ability to vigorously prevent an eager neighbor from making a mistake out of the corner of your eye, while a third person tries to interject with a question without any polite restraint. It's a balancing act that lasts for hours and by the end of the day, you're really exhausted. Pride would be the wrong word for me...it's more of a deep, calm satisfaction.

Knife-making Courses at the Outdoorcamp with old Craft Techniques

The Workshop at the Hut Table

Our specialty. And not everyone can do it. Building a knife outside or sitting by the fire in the evening is what the ancients used to do. They didn't have a workshop and they hardly had any proper tools. It was in their fingers, in their eyes, in their backs, sitting there and building and chatting by the fire is a unique experience even today. The hut table is also a substitute. Back then, nobody had the possibilities we have today. And yet - voluntarily reducing yourself to the essentials and daring to do it with your own strength is the modern adventure of building knives using old techniques. When the wind rustles outside the hut, the stove crackles and you spend hours using pure muscle and mental strength to build a knife that will easily last two to three generations if set up correctly and treated well. THAT is what fascinates us about it.

The leather knife pouch rounds it off and every time you're out fishing or even just carving or slicing bread, the faithful piece grips and cuts cleanly, bringing all the hard work back to life. So it's no wonder that you don't wear it out and let it rot away in the corner of the cellar.

Old Craftsmanship and new Perspectives

In a modern age like ours, living craftsmanship has become a rare, valuable commodity and a real asset. There is no app for it and anyone who has painstakingly built their own knife is more likely to show other craftspeople the respect they deserve than someone who just buys and consumes. They know what craftsmanship is from their own experience. It is honest and authentic, so full of attention to detail. It is a real art and an expression of his own creativity. And unlike the knives of today's Sami masters, who have to follow the very strict rules of their craft chambers in order to be allowed to sell them as Sami art, we are not bound by them.

We can build and shape the knife as we please and yet we are emulating the Sami tradition in the way we make it. By the way, the Sami just shake their heads at the nonsensical German nonsense about "cultural appropriation". If you don't call it a Sami knife and make it clear that you are honoring their millennia-old culture as an indigenous people who have been oppressed for so long, then you will certainly receive recognition for good craftsmanship. And so we honor the ancient knife makers of the Sami, who for so many centuries ensured the lives of their own with their artistry and craftsmanship. Because without a good knife, life in the Nordic wilderness was simply not possible... even today!

This year, we will once again be building knives in small groups and, if necessary, we will be happy to pack up the outdoor school mobile and come to your group. Click here for the knife-making courses at Trekk'n Guide. In the three-day courses, you not only make your own knife, but also learn a lot about handling simple tools and working with different materials.

Recommendations for further Reading

Do you want to plan your next trekking tour where you will use your self-made knife for the first time? Then take a look at my articles about the Laugavegur in Iceland or the Harz Witches' Trail. .

Do you want to know when there are new articles on my blog? Then follow me on Facebook, Pinterest or Instagram. I would also be very happy if you share my article with your friends.

Das sind wirklich wunderschöne Taschenmesser und wirklich toll, dass es sowas auch für Kinder gibt. Entgegen der Meinung, Messer gehören nicht in Kinderhände, ist es eher eine Frage der Übung und der Heranführung. Wenn der Umgang und die Gefährlichkeit erklärt wird, können auch Kinder mit einem Taschenmesser gut und sicher umgehen.

Hallo Werkzeugfan!

Vielen Dank für Ihr Kommentar und schöne Grüße auch von dem Autor des Artikels, Christoph Maretzek. Wir sehen es genauso. Wenn Kinder an Werkzeuge richtig herangeführt werden und klare Anweisungen bekommen, dann klappt das auch. Kinder lernen so schnell. Der Ausbilder Christoph hat da wirklich ein gutes Auge und Händchen… nicht nur für Werkzeuge, sondern auch mit den Kids, die nach seinen Kursen oder outdoor Kids Camps alle mit strahlenden Augen nachhause kommen.

Schöne Grüße

Mareike